Wren Library

Cambridge, UK, 1695

“The Wren Library was completed in 1695 under the Mastership of Isaac Barrow, who persuaded his friend, Sir Christopher Wren, to accept the commission as Architect to the project.” (15)

The Location

The Wren Library was built as part of the Trinity College of the University of Cambridge in London in the United Kingdom.

The Client

The Wren Library was designed for the Masters and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge by the architect Sir Christopher Wren in 1676 which was completed and opened in 1695.

The Wren Library was designed for the Masters and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge by the architect Sir Christopher Wren in 1676 which was completed and opened in 1695.

The Story

It was built because the previous library that stood in its place was deemed too structurally weak to be able to house the growing amounts of books and manuscripts it took in, growing from 500 or 600 volumes around the year 1600 to over 2700 volumes (composing of at least 500 manuscripts and at least 1500 printed books) over the next 50 years. (16) A fire had also burned down the roof of this library (along with some of the volumes) and “Bishop Hacket’s bequest of his personal library in 1670” made the matter of building a new library more urgent. (16) Two classical designs were created and submitted by Wren, one circular and one rectangular, and ultimately the rectangular design was chosen(17) which "consists of one great compartment 12m wide, 63m long and 10.6m high. It has projecting bookcases and wall cases down each side forming 13 bays.” (18) and built. As stated by the Trinity College website(19) today the Wren Library holds about 1250 medieval manuscripts, 750 incunabula, over 70,000 books printed before 1820, modern manuscripts and archives.

It was built because the previous library that stood in its place was deemed too structurally weak to be able to house the growing amounts of books and manuscripts it took in, growing from 500 or 600 volumes around the year 1600 to over 2700 volumes (composing of at least 500 manuscripts and at least 1500 printed books) over the next 50 years. (16) A fire had also burned down the roof of this library (along with some of the volumes) and “Bishop Hacket’s bequest of his personal library in 1670” made the matter of building a new library more urgent. (16) Two classical designs were created and submitted by Wren, one circular and one rectangular, and ultimately the rectangular design was chosen(17) which "consists of one great compartment 12m wide, 63m long and 10.6m high. It has projecting bookcases and wall cases down each side forming 13 bays.” (18) and built. As stated by the Trinity College website(19) today the Wren Library holds about 1250 medieval manuscripts, 750 incunabula, over 70,000 books printed before 1820, modern manuscripts and archives.

The Architect

Originally interested in mathematics, astronomy, physics and physiology Sir Christopher Wren turned to architecture when noticing that there was a huge lack of “serious architectural endeavour in England” after English architect Inigo Jones died.(20)

There were perhaps half a dozen men in England with a reasonable grasp of architectural theory but none with the confidence to bring the art of building within the intellectual range of Royal Society thought—that is, to develop it as an art capable of beneficial scientific inquiry. Here, for Wren, was a whole field, which, given the opportunity, he could dominate—a field in which the intuition of the physicist and the art of a model maker would join to design works of formidable size and intricate construction. (20)

There were perhaps half a dozen men in England with a reasonable grasp of architectural theory but none with the confidence to bring the art of building within the intellectual range of Royal Society thought—that is, to develop it as an art capable of beneficial scientific inquiry. Here, for Wren, was a whole field, which, given the opportunity, he could dominate—a field in which the intuition of the physicist and the art of a model maker would join to design works of formidable size and intricate construction. (20)

The Location and Daylighting

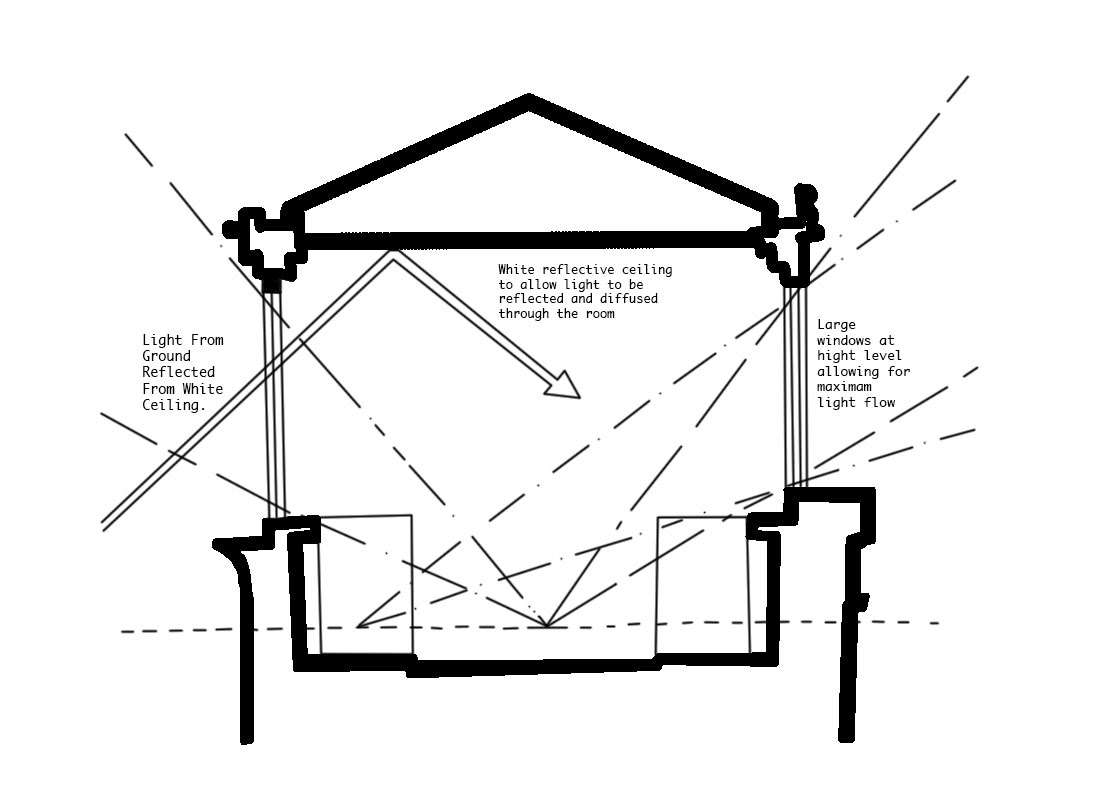

Due to the library being located in an urban area in the northern hemisphere which receives less annual sunlight than those closer to the equator it is important to note that the library took in ample daylight. Not only focusing on diffuse light and sunlight Wren made sure to note and include light reflected from the ground into the library by taking advantage of the vast fields that were on either side of it. It is possibly because of the location of the library and his consideration for the function of the building that he designed it to maximize the amount of light the users could receive in a time before electric lighting existed. It is a great example of an early daylighting design.

Due to the library being located in an urban area in the northern hemisphere which receives less annual sunlight than those closer to the equator it is important to note that the library took in ample daylight. Not only focusing on diffuse light and sunlight Wren made sure to note and include light reflected from the ground into the library by taking advantage of the vast fields that were on either side of it. It is possibly because of the location of the library and his consideration for the function of the building that he designed it to maximize the amount of light the users could receive in a time before electric lighting existed. It is a great example of an early daylighting design.

The Critique

The Wren Library was advanced for its time and “has been studied as a prototype of this period since it initiated a rethinking in library daylighting”(18). This makes most of the factors that contribute to a good daylight design applicable to this 1675 project.

To begin with, the library was built before the invention and implementation of electric lighting which only came about in the late 1800s. (21) Due to this, energy consumption at the time would not have been applicable. Today the library is equipped with, as stated by the group that installed lighting into the library David Powell & Partners (15), is general lighting, aesthetic and task lighting and emergency lighting. Due to the nature of the library’s design with its large windows it keeps energy consumption at a minimum as general lights do not need to be switched on during the day. Given that the library was opened to users from 9am until 5pm before the Covid-19 pandemic hit the globe in 2020 (now 12pm to 2pm) it would have saved a lot of energy because there was little need for it to be accessed when it became dark outside (excluding winter when sunset would be at about 4pm). Aesthetic lighting, such as lights illuminating books and emergency lighting would be the contributors to energy usage. However, there is nothing that should be changed about this structure or its light fittings as they seem to be able to keep the amount of energy consumed to a minimum and therefore proves to be a rather sustainable design.

Given that the library has an east-west orientation it is something which architects are typically not fond about due to the difficulty in providing an even distribution of light. Despite this, Wren was cunning about his design. He raised the windowsill level along with the ceiling to allow all types of light entering the library to diffuse and illuminated book spines and the work plane between each bookshelf with unwavering light. (18) His method of using clerestories and light-coloured matt walls and ceiling not only spared the books which must be preserved of harsh directional beams but allowed soft and uniform light to spill through the whole building. This provided a DF 3% in the central corridor and as Datta A states, “the variation of Daylight Factors within each bay is also relatively small (0.5%- 2%) as compared to earlier libraries. This reduces the local brightness contrast and increases visual comfort.” (18)

Wren manages to create a modern atmosphere through the building’s play on contrast with the dark lower half containing the books, shelves and study spaces and light upper half that serves to illuminate the building with soft light and avoid glare. Though credit must also be given to the chequered pattern on the floor that reflected daylight and brought about some up lighting. Wren’s playfulness with light can be seen at the end of the hallways where he adds a stained-glass window with vivid colours to balance out the lack of colour.

Overall, that for such an early design this is an incredible representation of what good daylighting designs can be like. Wren used this project to show his capabilities as an architect and to show how harsh light can be turned mellow.

References

15. Wren Library interior c.1870, Trinity College, University of Cambridge [Internet]. The Victorian Web. 2012 [cited 2020 Oct 26]. Available from: http://www.victorianweb.org/art/architecture/cambridge/21.html

16. Dunn A. Andrew Dunn Photo - Architecture [Internet]. Andrew Dunn Photography. 2004 [cited 2020 Oct 26]. Available from: http://www.andrewdunnphoto.com/html/ThumbArchitecture.html

17. Watson K. Trinity College Library, Cambridge (Christopher Wren) - Paper House. [Internet]. Paper House. 2016 [cited 2020 Oct 26]. Available from: https://paperhousegroup.weebly.com/lighting-and-visual-comfort/trinity-college-library-cambridge-christopher-wren#

18. Wren’s Library – Trinity College [Internet]. College Projects, David Bedwell Partners. 2011 [cited 2020 Oct 22]. Available from: http://www.bedwell.uk.com/wren-s-library-trinity-college

19. TrinityCollegeLibrary1965. Before the Wren Library – Trinity College Library, Cambridge [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Oct 23]. Available from: https://trinitycollegelibrarycambridge.wordpress.com/2019/02/15/before-the-wren-library/

20. TrinityCollegeLibrary1695. Building the Wren Library – Trinity College Library, Cambridge [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Oct 23]. Available from: https://trinitycollegelibrarycambridge.wordpress.com/2019/03/15/building-the-wren-library/

21. Datta A. Daylighting in Cambridge Libraries: Shifting focus over time. In: FORUM-PROCEEDINGS- [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2020 Oct 23]. p. 453–60. Available from: https://www.sbse.org/sites/sbse/files/attachments/scholarships/023pDatta.pdf

22. WREN LIBRARY TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 23]. Available from: https://www.trin.cam.ac.uk/library/wren-library/

23. McKitterick D. The Making of the Wren Library. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press; 1995. 0–171 p.

24. Summerson J. Christopher Wren [Internet]. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2020 [cited 2020 Oct 23]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Christopher-Wren#ref8007

16. Dunn A. Andrew Dunn Photo - Architecture [Internet]. Andrew Dunn Photography. 2004 [cited 2020 Oct 26]. Available from: http://www.andrewdunnphoto.com/html/ThumbArchitecture.html

17. Watson K. Trinity College Library, Cambridge (Christopher Wren) - Paper House. [Internet]. Paper House. 2016 [cited 2020 Oct 26]. Available from: https://paperhousegroup.weebly.com/lighting-and-visual-comfort/trinity-college-library-cambridge-christopher-wren#

18. Wren’s Library – Trinity College [Internet]. College Projects, David Bedwell Partners. 2011 [cited 2020 Oct 22]. Available from: http://www.bedwell.uk.com/wren-s-library-trinity-college

19. TrinityCollegeLibrary1965. Before the Wren Library – Trinity College Library, Cambridge [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Oct 23]. Available from: https://trinitycollegelibrarycambridge.wordpress.com/2019/02/15/before-the-wren-library/

20. TrinityCollegeLibrary1695. Building the Wren Library – Trinity College Library, Cambridge [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Oct 23]. Available from: https://trinitycollegelibrarycambridge.wordpress.com/2019/03/15/building-the-wren-library/

21. Datta A. Daylighting in Cambridge Libraries: Shifting focus over time. In: FORUM-PROCEEDINGS- [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2020 Oct 23]. p. 453–60. Available from: https://www.sbse.org/sites/sbse/files/attachments/scholarships/023pDatta.pdf

22. WREN LIBRARY TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 23]. Available from: https://www.trin.cam.ac.uk/library/wren-library/

23. McKitterick D. The Making of the Wren Library. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press; 1995. 0–171 p.

24. Summerson J. Christopher Wren [Internet]. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2020 [cited 2020 Oct 23]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Christopher-Wren#ref8007